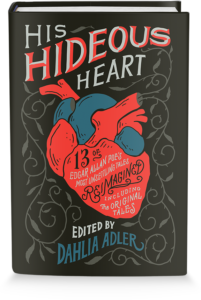

13 young adult authors… 13 heart-stopping tales… This collection will “delight longtime Poe fans just as much as readers who haven’t read the classics” (Beth Revis). I love Edgar Allan Poe. Ever since I was a tiny, moody, black-wearing preteen I have adored his macabre and melancholy works. Poe’s writing, not too well received during his lifetime, had an undeniable posthumous effect on modern gothic fiction. There are few, if any, gothic or horror writers today who can deny his influence on their work, and Anya Seton didn’t even try. She straight up opened her 1944 Gothic romance, Dragonwyck, with one of Poe’s poems and wrote him in as a character. Though he only appears in one scene, Poe pervades the novel. The “hero,” Nicholas, is obsessed with Poe’s writing—with his attitude towards death and the supernatural—that it actually defines his character. Dragonwyck is a fantastic example of modern gothic fiction: it’s lush and suspenseful. So, Ghosts and Ghouls, let’s get 19th century spooky and take a closer look at one of my all time favorite gothic romance novels. Dragonwyck is the story of a young farm girl from Connecticut, Miranda, whose life is upended when she accepts an invitation from one of her mother’s distant relations to be companion to his small daughter. Nicholas Van Ryn is the patroon of an old Dutch Hudson River Valley estate, where he lives with his wife Johanna, and his daughter Katrine. He’s fabulously wealthy, handsome, charming, and as cold on the inside as an iceberg in January. From the first time we encounter Nicholas, it’s clear that there’s something off beneath that Prince Charming veneer. We’re able to see what the naive Miranda, already introduced to us as a romantic at the beginning of the novel, is blind to: Nicholas is as sinister as he is charming, as secretive as he is witty, and the aristocratic facade that makes him appear so noble masks a character marred by paranoia, arrogance, fear, and leashed violence. Seriously, people, this is such a good book. Go read it, and then go watch the 1946 movie with Vincent Price in what has to be my favorite role for him. He really nails Nicholas’s ability to go from charming and tender to cold in a heartbeat. He could cut you dead with a word.

via GIPHY (I mean just, unf. So swoon-worthy. He might poison you with oleander, but it also might be worth it? Maybe?) Now as I said, Poe only appears in one scene of the novel, which does prove to be a pivotal scene when viewed after the fact. But he’s mentioned repeatedly from early on in the novel. He’s a bit like Chekov’s writer—if you’re going to mention the writer, and mention the writer, and mention the writer, eventually the writer ought to appear. It’s Nicholas who first introduces Poe in the text, referring to him only as “a startling young writer” whose work he greatly admires (43). Then later in the book he expounds in greater detail that to him “there is no beauty without mystery and shadow. There’s a young America author, Edgar Allan Poe, whose writings express [his] feelings perfectly” (73). Nicholas’s attraction to Poe’s work is one of our earliest clues about the dark corners of our romantic lead’s (yikes) psyche. He himself admits that he admires Poe’s work because it shares his own belief in the beauty of darkness and death. One thing that we are told about Nicholas in the novel, shortly after his marriage to Miranda, is that his mother died when he was 12, and that because of her death he cannot give Miranda the “type of goodness and love for which her heart yearned” because it “had not existed in Nicholas since he was 12, and his mother died” (211). What we are meant to infer from this brief mention, and from his rather alarming attachment to Miranda’s golden hair which so resembles his mother’s, is that Nicholas has serious mommy issues. I’m sorry. That’s terrible. But it is not entirely false and, more pertinent to my point, the death of Katrina Van Ryn was the catalyst behind Nicholas’s obsession with death. Given the Van Ryn propensity for temper and instability—they are described as being a “wild, strange lot with some kind of skeleton in their closet” (7)—and their arrogant preoccupation with strength and lineage, it is likely that Nicholas’s mother was the only one who showed the boy any affection, so when she died so took all the love out of his world. I say that not to exonerate what Nicholas will eventually do in the novel, but rather to explain the origin of his peculiar attitude towards death. And the source of his attachment to (however unwilling) and longing for not just Miranda, but her love for him. He’s a peculiar character. Completely despicable, and yet written in the margin of my reading notes is the question: “have you ever seen a lonelier man?” A sentiment Miranda echoes at the end of the novel. He’s like an empty, freezing void, desperate for a light and a bit of warmth. Desperate for a connection. Which is why, when Poe finally makes an appearance in Dragonwyck, Nicholas is so desperately disappointed. He expects to find a kindred spirit, someone who despises death and seeks to defy it at every turn, someone who understands the emptiness of life, the pointlessness of it all if you can’t overcome death and find some shred of immortality. And someone who was “unhampered by petty morality or the conventional attitude toward evil as Nicholas knew himself to be” (252), and could understand the measures a man must take to achieve immortality. Instead, Nicholas finds a ragged man, old beyond his years. A drunk, wallowing in grief as his beloved wife dies in the other room. Rather than standing up to death like a lion, Poe uses whiskey to drown his fear, and poetry to confront it. Fear is the keyword here, because it is Poe’s fear that Nicholas despises, declaring Poe to be “worthless” even as he admits to envying the other man’s dreams (252). The artist has failed to live up to the merit of his work. No affinity of the soul, all Nicholas gets out of his meeting with Poe is an addiction to opium, and the beginning of his own self destruction. See when it comes to fear, Nicholas is the king. There’s a reason that this novel is set against the background of the agricultural unrest in the mid-19th century in America that led eventually to the dismantling of old estates like Nicholas, which had until that point been host to tenant farmers. New laws eventually freed tenant farmers from their overlords by permitting them to buy their own land and no longer have to pay rent, thus removing one of the last vestiges of old world feudalism from the new world. All that was left after that was the slave trade. Unsurprising, again, that the novel is also set just at the cusp of the Civil War. Change, the decimation of the way of life that Nicholas’s ancestors had upheld for 200 years, the dwindling of his family line until he remains as the only male Van Ryn. Immortality is slipping through his fingers. Poe couldn’t give him the secret to eternal life, though opium let him “pierce the mist which separates us from reality” and make him “master of life and death” (341), which is what he truly desires. He only turns to the opium, though, after his son with Miranda dies, shattering Nicholas’s dream of a Van Ryn legacy, and Nicolas himself nearly dies when he is attacked by rioters in the city. More specifically, Nicholas shot a young boy point blank in the chest for throwing water on him and incited a riot that then ended with him getting struck in the chest with a brick, which left him “helpless before strangers and Miranda” (339). Unmanned, weakened, certainly not master of anything in that moment, let alone death. What fascinates me about Nicholas’s decline is how it relates to Poe’s presence in the novel. It wasn’t enough for Nicholas to exist as a character driven by what he perceived to be Poe’s philosophy of the world. There are plenty of villains and antiheroes bent out of shape by what Nicholas believed was a shared distaste for morality and “the conventional attitude toward evil.” But having Poe appear in the novel, having Nicholas meet him, forces Nicholas to confront his foibles. In Poe he sees his own weakness and fears, and spends the rest of the novel raging against what he saw that day in Poe’s house. The reality that he was mortal, fallible, and alone. He can’t continue on as the “master of the universe” we meet at the beginning of the novel, and be defeated at the end of the novel by the righteous, combined moral forces of Miranda and the good doctor Jeff Turner. He has to be defeated by himself. It’s one of the reasons I love this novel. Yes, Miranda is a proper gothic heroine, and yes, the noble, dashing young doctor sweeps in to save the day, but in the end they don’t destroy Nicholas and save the day. They don’t even expose his treachery to the world! Seton subverts that element of good triumphs that we see in some of the classic gothic romances. Instead Nicholas quite literally destroys himself. Depriving them of the pleasure and, ironically, casting himself as a hero in the eyes of the world. Securing a legacy for himself that he never lives to see, and pushing Miranda and Jeff out of the spotlight. I won’t give away the ending of the novel in detail because I’m hoping that if you’ve never read it you’ll give it a try! But I will say that if you love difficult moral quandaries, that’s basically the purpose of this novel. And Seton leaves you with a doozy. So, not only does Dragonwyck feature a very significant cameo from the tragic Poe himself, it’s also chockablock with dramatic landscapes, suspense, murder, romance, the aforementioned moral quandaries, and one very big, beautiful, spooky house. When you run out of Poe to read on this most wondrous of Poe Days, consider picking up Seton’s gorgeous gothic romance. Written in 1944, it’s not without its warts (reader beware of some awful fat shaming and racism, for starters), but it is a fantastically moody, dark example of the modern gothic.

via GIPHY